Visual artist; paintings, graphics, tectons,

videos and mixed media works

Lives and works in Tampere, Finland

CONTACT INFORMATION

33270 Tampere, Finland

Kalkun viertotie 2 C 9–10

33330 Tampere, Finland

The Art of Lars Holmström, 2019

CONSTRUCTIVISM,

STILL FULL OF QUESTIONS

The time is long past when it was debated whether compositions of geometric shapes were real art or whether expressive brushstrokes were ultimately the core of Art. And of course whether an artwork had to represent something similar to the perceived world, i.e. be figurative, or whether it sufficed for the artist to assure that colours and forms as such are meaningful. The heated disputes on where the visual arts end and architecture/technology/the environment begins or what materials are suitable for artists to use seem no less distant.

Lars Holmström’s art is in the midst of a mature period in which the pluralism of both its means and meanings are normal. It is also normal for a constructivist artwork stressing pure structures to be understood as something much more than an explicit jigsaw puzzle of colour and form. It is now understood that a subjective, intuitive element belongs to it and gives it its emerging motifs.

In his oeuvre, Lars Holmström has addressed the whole scale of constructivism, from paintings, prints, reliefs and sculpture to architectural paintings and constructions. He has made prominent landmarks, such as Continuus 4–4, an eight-part colour art work in Rantatunneli tunnel in Tampere, Gemma, a five-part sculptural installation on the wall of an apartment block in Vuores, and Ainon ornamentti (Aino’s Ornament), a painting executed directly on prefabricated building elements in the Pajalankulma parking facility in Järvenpää.

So is everything easy and problem-free for this long-standing constructivist?

I would hardly think so. Holmström often makes series of works that individually address completely different problems of form and colour. A distinct style could be developed from each series, perhaps even a complete oeuvre as if there were several artists instead of just one. The Quadratum series is a classic oscillation of superimposed squares; Iulius considers the perceptions of movement in asymmetry; Triplex (Tripartite) embeds three different elements together; Regio (Direction) turns parts of works with the aid of diagonals and centres of gravity; Turbo (Vortex) moves an ellipse that could be a circle; and the crafty Praesto (I specify) is a series of digital prints asking what optical alterations from sharp to blurred mean, as if we were looking at one world with one eye and another world with the other eye. Praesto can also be seen as camera lenses, one focusing to produce a sharp image while the other creates a light-haze impression. The medium thus monitors itself and an outside observer can consider which is aesthetically more valid, the naturalistically distinct or the impressionistically blurred. – I can guess the most common answer to this question.

Holmström’s works pose seemingly simple questions, but that is where their depth lies. In order to get a grasp of the meanings of the works, the viewer cannot stop to assess pure structure and bright colour but instead has to take measure of his or her own perception and the experience that it creates. A gently swaying bridge is built between the artwork and its viewer. A work that looks fixed and solid will thus not remain visually in place and turns into a wanderer whose next step is hard to anticipate.

Markku Valkonen

Lars Holmström, 2015

SYSTEM AND DEVITATION

The art of Lars Holmström is investigative by nature. It appeals to perception more than to emotion. Artworks are highly materialistic, the relief paintings in particular, which are tangible objects in real space. The works hold the gaze of a viewer without leading it elsewhere. The essential elements are colours and forms, which form the basis of an artwork, and are infinitely enticing to Holmström. The study of them forms the logical, methodical foundation of his art.

Holmström´s recent body of works has included paintings and prints as well as public works related to large-scale construction projects. His constructivism is particularly suitable in those. Digital graphics utilizing photography has brought a more unconstrained touch into his pictures. There are several subcategories to digital graphics ranging from computer generated graphics to prints made of pictures scanned from real objects. Judging from the spectrum of his methods Holmström seems to have examined nearly all the options this tool has to offer.

Using photography also means that figurative elements are carried into Holmström´s works, which is otherwise uncharacteristic to his abstract art. Digital image is often the main subject matter of the work, although it is used mainly as a structural element, not as an image itself. The prints in the Mysterion series are based on geometric forms found in stone floor paving. Holmström allows the irregularity of it to guide him also in colour design as he puts to use the imprints on worn-out stones. In the end, however, he reverts the figurative elements to visual beings, which, estranged, serve first and foremost the overall visual orchestration. Even the use of abundant materials results in a controlled whole.

Occasional viewer may notice the beauty of the surface and construction as such, while a more attentive observer may also detect various systems, deviations and planes one within the other. They are pictorial epiphanies, consequences of deliberate work processes refined into a technique in the hands of a professional artist. But there is also a strong intuitive side in these processes. Holmström talks about source images, visual starting points, which gradually generate into actual works. These starting points are very likely some sort of movements in consciousness, observations before the subject is conceptualized. Maybe they are born while looking at life through art. In any case, they put forward the process of form-giving, which does not necessarily stop at the finished work, but continue its flow in the mind of a viewer.

One feels that this is exactly what it´s supposed to be.

Tapio Suominen

Tampere Art Museum, Tampere, Finland

Chief Curator

THE UNSEEN FOR US

DOES NOT EXIST

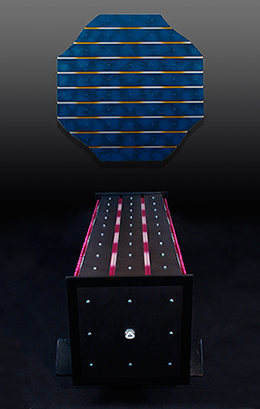

In his essay In Praise of Shadows Japanese author Junichiro Tanizaki contemplates visible and shrouded beauty. He writes: “The unseen for us does not exist". For Tanizaki shadows that dim the light and blur the contours have their own special quality. They allow the ones in the shadow to remain there and retain their inherent beauty. An artwork contains a hidden quality, an essence withdrawn in shadows, and it must be accepted as such. The intentions of an artist do not necessarily, if ever, meet with the expectations of a viewer. It is not even important, if we deny the existence of the invisible, as Tanizaki does. It is difficult to empty an artwork of its meaning and contents, its position and relation to the traditions of art as well as to its social existence. Everything being connected to everything else calls for the exposure of all these connections. Nevertheless, each artwork contains the unseen, which does not exist for us, unless it is handed to us in interpretations, analyses and theoretic concepts. When Lars Holmström, painter and graphic artist, names one of his artworks Sarkofagos (2009), the viewer must believe that the name bears a meaning and that the medium, the work itself, carries a message. None the less, there remains also the invisible in the work, something that does not exist for us. Holmström does us a favour by interpreting his work. The initial impulse came from a Chinese aphorism: “The best gift for a 60-year-old man is a coffin." He found it in an exhibition in Museum Centre Vapriikki in Tampere and realized that soon he himself would turn 60. Sarkofagos is both a constructivist artwork and an object suitable for mass production. He has used his own measurements to make it a fathom long (about 183 cm) and wide enough to fit a person, but from inside it is barely spacious enough to hold a corpse. The rectangular object is open from both ends in order to facilitate the placement of a corpse and to secure its tight closure. The surface of Sarkofagos has a two-layered structure, and it has been painted with black and grey metallic paints. Energetic colour areas of white and empire red radiate from the depths. Mirror image of the viewer is reflected from the metal bolts on the surface.

It is permitted to laugh at Death.

Sarkofagos, however, is not merely an object with an imaginable practical function. It is also an artwork, in which culminate the various stages of development and change in Lars Holmström´s expression. After he refined his style under Concrete art and Constructivism he has gradually detached himself from the geometric lyrics of his paintings and serigraphies. He has moved towards three-dimensional, sculptural pieces, the plasticity of which is completely different from the surface-bound, three-dimensionally unfolding paintings and prints.

The work XXIII from 2006 is a relief painting, which already demonstrates the spatial and material solutions brought further in Sarkofagos. The work is massive but light. By its structure it reminds us of an old elementary school handicraft where you pass lengths of material over and under one another. In XXIII the passing is done with solid vertical masses and thin horizontal arrow-like rods. Although the work may bring to mind school memories from decades back, it does not mean that they are visible or perceivable by everybody. They are associations demonstrating how the recipient may confront the work and enable the unseen to exist. Tying the work in with the viewer´s, i.e. interpreter´s own history does not make it more "real" than when it is allowed to be a physical object an sich, without any connotation.

Lars Holmström is known as a consistent serigrapher with a clearly recognizable expression.

Digital technology and new means of image processing have opened new dimensions for him to do his graphic work. He has named his recent prints digital graphics. In his works he has used various graphics programs and three different methods. Constructivist works follow the line of his serigraphies. At the moment, synthetic methods combining originals and photographs offer him the most interesting options. They open up the best means of expressing various visual goals.

The three works in Ritualis G –series demonstrate how rich is the outcome achieved by this method. The starting point of each work has been a commonplace object, which has been scanned onto a computer screen, a kind of an operating table. He then has played the part of a surgeon or an instrument nurse and cultivated his materials further. Tools and incisions are carefully deliberated and the result is surprisingly aesthetic. Although the works in the Ritualis-series do not intentionally seek to create optical illusions, they still open up fascinating depth dimensions for a focused viewer.

The series of digital graphics called C from 2004 appear to be a logical follow-up for his strictly geometric serigraphies. The works test the eyes of the viewer. They act as stereoscopic pictures, where movements of the eyes make three-dimensional forms pop into view. Forms can emerge towards the viewer or recede into the background. The works in C-series test the recipient´s stereoscopic vision, the very image how the work is perceived. With these particular works Tanizaki´s sentence becomes true: the unseen for us does not exist.

But supposing the viewer actually sees what does not exist?

It results in a genuine heureka experience, the one that reveals the deep, gratifying force of the art itself.

Maila-Katriina Tuominen

Journalist, Culture and Human rights

Tampere, May 2009

— Quotation: Junichiro Tanizaki: Inei raisan (1933-34), translated in English by Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker: In Praise of Shadows (1977)

— Jyrki Siukonen: Varjojen ylistys, Taide Publishers, Helsinki 1997

— Eduard Klopfenstein: Lob des Schatten

— Julia Escobar: El elogio de la sombra